The Audio Drama Renaissance

Last updated on March 13th, 2023

Discussing the Sweet Spot of Audio Drama Renaissance Between 2014-2016

First things first: what’s a Renaissance?

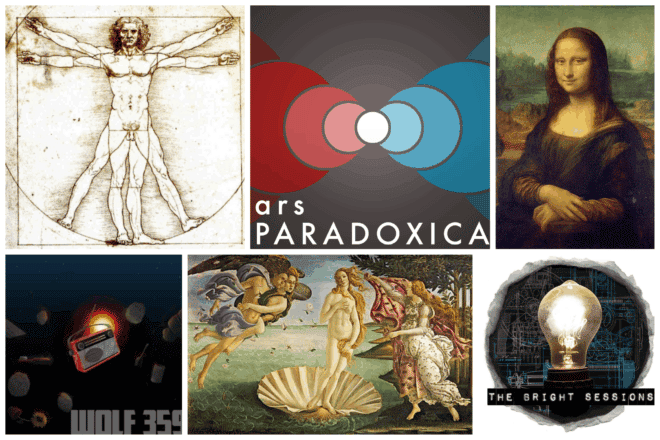

For something to be deemed a renaissance era, it must deploy an air of new discovery, new philosophies explored in every angle possible and, above all, introduce us to new art and the new artists that made it. The era of the first Renaissance in Europe covered the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries, which gave us the likes of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo–and maybe some other ones the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles weren’t named after.

If you know basic art history, you know The Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, fantastical and yet distinctly human perspectives of religion, beauty, creation, and strife. The Renaissance aimed to understand the very core and purpose not just behind art but why we make it in the first place, and I can’t help the feeling that podcasts had a very similar era between 2014 and 2016. In fact, a major help for this article, Newton Schottelkotte of Inkwyrm and Where The Stars Fell, neatly categorized this as the second phase of the audio drama era.

I’ll admit I’m using very flamboyant terminology here. The quality of art is a very subjective topic, so throwing out the word “renaissance” so loosely beyond the aesthetic appeal further paints me as the pretentious enthusiast. I already know I am. But if Disney gets to call the years from 1989 to 1999 their “renaissance” then why can’t I employ the term?

To put it simply, a renaissance is simply a time when great artists made great art, and during those two years I’d be lying to myself if I said that exact thing didn’t happen in the audio drama community.

Okay, what’s the Audio Drama Renaissance?

I personally like to call this period a “renaissance” because I feel like the shows published around this time set some sort of standard of quality for years to come while never trying too hard to emulate a preexisting style. There’s nothing wrong with a template, but it’s breaking out of that “Night Vale but with a twist” spectrum that let these shows go from good to great.

Read more: A History of Night Vale Presents

You could say that the existence of Titian’s Venus of Urbino coupled with Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus justifies the existence of the other, and there are similar depictions of masculine nudity in both Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and Michelangelo’s David.

Mark Twain put it best when he wrote in his autobiography, “There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope.” And the same could be said for audio drama that shifts between the most outlandish of concepts to repackaged versions of things we’re already familiar with.

Kind of like how Half Life inspired a league of innovative first person games, Welcome to Night Vale and Thrilling Adventure Hour are undeniably our Medici Family. Beating on about Night Vale’s influence on audio drama is a dead horse that I don’t even poke into, but going through a whole article without mentioning the impact the show had on the existence of podcasting as a whole would be a major disservice to the podcast community or whoever reads this far.

And besides, it’s the power of having multiple muses that makes any Renaissance really matter.

“Of course, what’s interesting about making something like this show is that you don’t just bring in your influences from one genre into something like this – inevitably your writing gets filtered through all the pieces of fiction you love and carry with you,” Wolf 359 writer Gabriel Urbina told me during an interview I had with him in February of 2015.

“So I’d say that Wolf 359’s primary influence is Farscape, but there’s also a lot of, say, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Stephen Sondheim musicals, and Catch-22 kicking around in there. Heck, if you know where to look, there’s a lot of My So-Called Life in Wolf 359. So you’re always bringing in outside perspectives to your favorite genre. That’s half the fun.”

Let’s take a moment to discuss science fiction, a genre that has birthed the likes of giant sandworms and lightsabers and even after all this time still has a massive hold on audio drama fiction.

2014 to 2016 had an absolute plethora of sci-fi audio dramas, but each one cultivated to a variety of tastes. EOS 10, Ars Paradoxica, SAYER, and Wolf 359 are all under the same umbrella, but they each have polarizing differences that appeal to a variety of people.

EOS 10 is a quaint hospital drama, Ars Paradoxica is intelligent and complex time travel narrative, SAYER is an unapologetically terrifying glimpse into a sterile dystopia, and Wolf 359 is an excellent blend of comedy and tragedy with a down-to-earth cast of misfits.

All audio dramas, all under the space/science fiction genre, all with distinctly different DNA that make their identities clear from the first episode.

Though dramatically different in terms of humor, style, and plot, these shows do have quite a few similarities in a meta sense.

All of these shows at some point shared the following: successful crowdfunding, a surge of audience creations ranging from art to fan blogs, and the liberty of at least one or two live shows. I can’t help the feeling that this time frame showed that there was not only a creative outlet for smaller artists to pursue, but a (somewhat) profitable one at that.

In fact, my interest in audio drama wouldn’t even exist if I hadn’t been sneaking peeks of my podcast app feed in between my high school classes, completely captured by this new world of art I’d been oblivious to for so long.

A feeling stirred in me right then that this was what the community was capable of: art that was both a technical feat and had real depth to their stories. I felt I had a duty to discuss it in more detail the same way philosophers would dissect William Shakespeare and Picasso.

Though it certainly happens now, I do know that podcast fandoms were becoming much more of a common occurrence. So much so that I could attend a convention gathering with the Wolf 359 crew at 2015’s DragonCon where I got to talk to the writers and actors myself in a giant patch of grass outside the building with fellow fans.

If I had the confidence I would have asked Doug Eiffel’s voice actor Zach Valenti to autograph my forehead instead of my notebook.

When can we call a podcast successful?

The question remains for a few people: why a podcast instead of a proper TV series or movie? And is choosing audio drama as the format of choice considered settling for the easiest, most affordable option instead of choosing the platform you truly want? Well, yes and no.

During my talks with podcast producers, I’ve seen that plenty of them view their works as something that functions best as audio dramas first and foremost. Not that dialogue heavy shows like these can’t be converted into comics or books, but to assume podcasting is just a last resort for storytelling feels like such an insult to what the medium can provide.

Not to mention that building off inspiration from the likes of big time movie franchises and television is all part of the inspiration process.

I remember gossip going around about podcasts being adapted into films or TV shows, clearly a byproduct of all the hype, but I think Urbina said it best when describing the duality between audio based entertainment versus more traditional formats like live action TV:

“. . . it’s very important to us that we’re not just making Wolf 359: The TV Show and then hatcheting that into a radio format. We want to feel like the stories are consciously made to fit with radio, not like you’re just listening to a TV show someone is watching in the next room. And a big part of that is the stories you go to . . . audio dramas are very dependent on the fact that you’re being denied a lot of information about what’s happening in a situation . . . You’re constantly behind, then you’re catching up, then elements you didn’t know were there are pointed out, etc.”

Gabriel Urbina

Urbina cited iconic season one episodes like episode nine’s “The Empty Man Cometh” and episode eleven’s “Am I Alone Now?” as standout examples. “Your entire understanding of what’s happening is constantly being adjusted and revised as the scenes go forward,” he added. “And you want stories that revolve around that.”

This comment sticks out to me specifically because I think it squashes the assumption that television adaptations are the definitive way of “making it.” In reality, some art forms work best how they currently exist. Podcasts rely so heavily on the product of imagination in ways that television doesn’t accommodate.

The Bright Sessions producer Lauren Shippen had a similar sentiment when I interviewed her in February of 2017. “The reason for making The Bright Sessions an audio drama was two-fold,” Shippen said. “First, there was the practical reason: making an audio drama is far less expensive than making something for film. I needed to be able to do every step myself – the writing, the recording, the post-production – on a tight budget.”

And even with limitations on the physical appearances of the characters, art interpretations were at an all time high. Trying to guess the base physical descriptions of main characters had become a game of sorts and certain headcanons became popular among fandom spaces.

There’s definitely something to be said about the relationships between creator and audience that’s been bred from the innovation of social media and purely fandom based spaces like Tumblr and Twitter. After all, with no real marketing budgets or traditional ads, so interesting fanart was the next best thing when it came to getting the word out about an interesting new show.

For audio drama creators, a fandom contributor with a decent following is the equivalent of a commercial–if not far better than any old ad. These shows weren’t made by the biggest studios, seldom ever going beyond recordings in a friends padded sound room with the AC off, creating this sort of closeness that unknown artists like myself found incredibly endearing.

These were small actors, low budgets, closely knit creative groups of roughly five or so friends working together to make the ultimate passion project with maybe a slight chance they might get some revenue out of it.

Is there a Renaissance happening right now?

I feel that entirely depends on who you ask. With podcasting becoming such an accessible art form, it did inspire a bit of an overabundance problem. I’ve studied audio drama trends for years now and I’m barely up to date on all the new shows debuting every month.

Every week it’s a new horror show, in the next two days some sort of improv comedy, and the years after that we always see someone’s take on the cryptid/paranormal hunting genre . . . or maybe something in space. The barrier to entry on podcasting is a whole other ballgame. In the traditional entertainment industry, it’s all about who you know; in podcasting it’s usually who finds your casting call first.

There’s naturally something to be admired about art that deliberately tries to step outside a mold that’s already been proven to work. Yes, we’ve seen that Lovecraftian horror towns are a shoe-in for a roaring fanbase, but who’s to say a slipstream interpretation of Boston won’t work?

At the time, no one had pitched dystopian A.I.’s running worker bee cities, a secret organization that fakes deaths, or dysfunctional superpower therapy, the latter of which not only turned out amazing but had such overwhelming support creator Lauren Shippen has continued and expanded the world of The Bright Sessions as novels.

I have a very fond but distant memory of when Shippen contacted me when I started up the first ever edition of Podcake, pitching me her audio drama idea back when The Bright Sessions was only barely a season long, looking for my input as a “podcast virtuoso” (her words, not mine). And to think I can see her name now, gracing the sides of a Barnes and Noble bookshelf is the kind of surreal experience I never thought I’d get to have.

The point is, audio drama could easily be the first step to even bigger and better things. I think it was that two year Renaissance that triggered a spark in everyone. Though it might be personal tastes, it’s that strike between style and substance appearing in such a period of time that made it feel like this bold artistic movement that had potential to grow–and grow it did.

There may not always be enough room for the best podcast but a considerably good one isn’t too far off from starting the trend all over again. Enough breakout artists make their debut today or tomorrow, and we might have a second Renaissance on our hands.

(Editor’s note 10/15/21: Edits have been made to correctly attribute the research on audio drama errors to Ella Watts via the BBC.)

Comments

Comments are closed.