How to Audio Drama: Script Formatting

Last updated on August 31st, 2020

I did not go to film school. I did not go to school for theater. I have not taken a screenwriting class. The same applies to my co-writer. So, how did we write our scripts? A lot of mistakes.

A lot of mistakes that you can learn from.

Film and theater students might disagree, but in my eyes, there’s no single right way to write a script for your audio drama. There are, however, many ways not to write a script.

What to do

The most important thing to do when writing a script is to make it clear to everyone involved–to you, to any other writers, to the director, to the actors, and to the sound designer. You don’t have to know the most traditional or classic way of writing a script for it to be understood by your team. The best way to go about this is to ask your team what makes the most sense to them.

Let’s look at two of the most classic formats when writing a script. One of the most common you’ll see is taken from traditional screenplay formats, and centers the dialogue:

Example 1

FADE IN: Wil sits at their desk, typing.

SFX: Room tone, typing on a laptop.

WIL

(Thoughtfully)

Hmm . . . yeah, I think this is a good example of writing a script.

Another format you’ll see often left-justifies everything and uses colons to separate the character and their dialogue:

Example 2

FADE IN: Wil sits at their desk, typing.

SFX: Room tone, typing on a laptop.

WIL (thoughtfully): Hmm . . . yeah, I think this is a good example of writing a script.

Both of these formats work fine. If one of these works for you, use it. If you think you have a formatting idea that makes more sense to you, talk to your team, but it’ll probably be just fine. What matters is that it’s easy to read and it makes sense.

Every team is different. When I’m doing sound design, I prefer stage directions to be written as though they were for a film or TV show (“Wil sits at their desk, typing”). I’ve worked with sound designers who would want the sounds actually described (“SFX: Room tone, typing on a laptop”). The best way to know what your sound designer needs is to be direct and ask them.

I do highly recommend writing stage directions, even when the audience won’t necessarily hear every action that they would see. Treating your audio script like a script for a visual medium increases the sense of realism, and often informs both actors and sound designers on the physicality of a scene. You might not hear the sound of someone smiling, but you will hear it in their voice.

At the start of your script writing process, it’s unlikely–and inadvisable!–to have your audio drama cast. This means that when writing, you should make things as clear as possible for those involved without being distracting. You do not need tone direction on every line, but you should give tone direction on lines that can be read in several different ways if you want the actor to go for a specific delivery. If something is yelled, specify. If something is whispered, specify.

What to do (for extra credit)

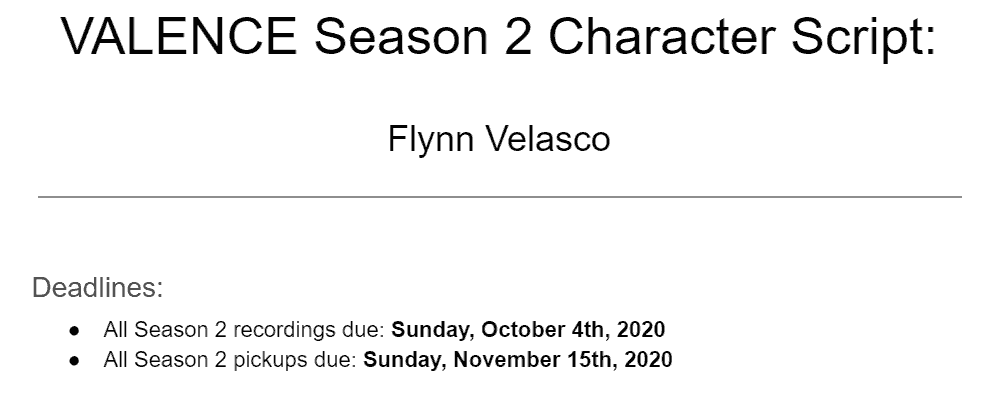

Once all of your scripts are completed, individual actor scripts are a great way to give actors information they’ll need for your production. For our second season of VALENCE, we made cast scripts for all our major, minor, and ensemble (more than ~5 lines) characters. Each individual cast script has a cover page with the following, and our show’s art for season 2:

Having the dates right on the cover page means they’re clear, and actors can reference them whenever needed. On our second page, we give some other guidelines that are specific to our production, including a link to our reporting policies, how many takes of each line we’d like, etc.

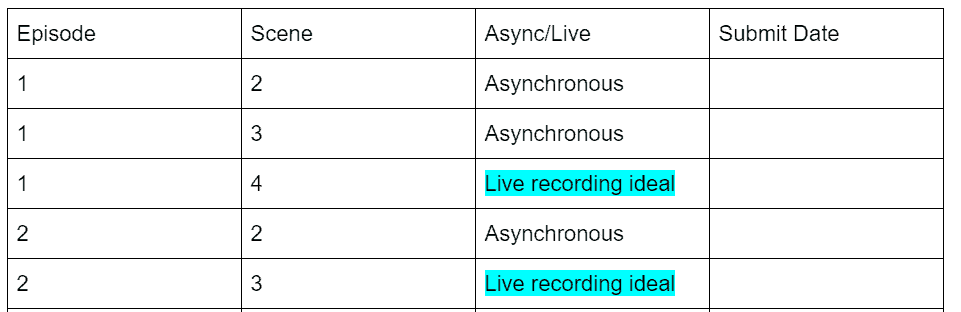

But then comes the real crown jewel of the individual cast scripts: the checklist. Starting on page 2, we have a checklist of every single scene that character is in, how it’s being recorded, and a space for them to check off if they’ve submitted the audio:

Having a checklist helps actors stay organized, and helps them set expectations as they read the script. VALENCE uses both live read recordings and recordings the actors do asynchronously, which we’ll discuss in a later edition of How to Audio Drama. This means that the column might not apply to you, depending on how you’ll record–but it’s integral to our production.

Another thing you can do for the individual cast scripts is use them to add more direction for a specific character if that character keeps their motives secret. One of our characters typically has much more on his mind than he’ll say out loud, and he’s also often lying. Putting the background information in the cast script helps an actor understand what’s really going through their character’s head without cluttering the script for the other actors.

What not to do

A quick list of things that I’ve seen writers do that you should avoid:

- Do not write your script in a spreadsheet. This is very weird, and it’s hard to read–but mostly, it’s just very weird.

- Do not give direction in every single line you write. Trust your actors to know how most lines should be delivered based on context–but also allow your actors to surprise you with some deliveries.

- Do not write in prose style, as you would a book. It’s too difficult for actors to see their lines clearly.

- Do not distribute your finished scripts as PDFs unless requested by an actor; PDFs are very difficult for screen readers and other accessibility tools.

- Do not write unclear directions–things like, “Go buckwild on this line”–unless you know an actor really well.

- Do not ignore your cast or crew when they ask for different formatting, clarity, etc. on a script. Just because a script is “perfect” for you doesn’t mean it’s perfect for your team.

What to use

There’s plenty of script writing software out there, but all of the options I’ve come to love are free, easy to use, and probably things you already use. Final Draft is the industry standard software in film and TV, but honestly, audio drama creators don’t have to live like that. It’s unnecessarily expensive, and unless you plan on eventually going to film or TV, you’ll probably use it so seldom that I can’t fathom justifying the cost. Instead, here are some free programs that are just fine.

Google Docs

A simple Google Doc is likely the best tool for you to use for script writing. It’s a free, familiar product that most people have worked with. It allows for collaboration, and even more importantly, it allows for comments. This means that you can quickly and easily write a comment to clarify pronunciation, give alternative versions of lines, or give actors reminders on delivery if they’re struggling with a line. Make sure you think closely about who has access to do what on a script before sending it out; if everyone is working from the same Google doc, and everyone has editing powers, things might get confusing.

Microsoft Word

Microsoft Word is Google Docs but more expensive and less collaborative. If it’s what you’re used to, there’s nothing wrong with it, especially if you’re writing alone.

StudioBinder

If you’re looking for a professional-grade script-specific program that will guide you through a traditional screenplay format, StudioBinder is hard to beat. It’s a comprehensive online tool that also includes tools for scheduling, headshots, and more. It’s a robust program that luckily has plenty of video tutorials. I used StudioBinder for the initial scripts of VALENCE season 2, but I found it too frustrating to use when collaborating and editing together. If you’re writing alone, this might be a great program for you. They even create guides similar to How to Audio Drama, but obviously focusing on visual media. As always, this isn’t sponsored; I just think StudioBinder is neat.

How to Audio Drama is our weekly column documenting every piece of information you’d need to start your own audio drama (aka fiction podcast). The series can be read in full, or read volume by volume. You can use our table of contents to find each How to Audio Drama installment, and you can submit questions to our monthly How to Audio Drama advice column.

3 Comments

Pingback "How to Audio Drama" Table of Contents | Discover the Best Podcasts | Discover Pods

Pingback How to Audio Drama: Your Outline | Discover the Best Podcasts | Discover Pods

Pingback How to Audio Drama: Writing Exposition | Discover the Best Podcasts | Discover Pods

Comments are closed.