Untold: A Struggle for Justice

Marooned in the front of our classroom, the white haired gentleman–the calm at the centre of an ongoing media storm revolving around his brother, the subject of his podcast Untold: The Daniel Morgan Murder–seemed all but lost in a classroom of wannabe reporters. The presiding lecturer was a gentle giant of sorts: stood adjacent to the mystery guest, his chest out, his voice became emotional. “This is Alastair Morgan, my mate of thirty years, who has spent half his adult life campaigning for justice. You can ask him anythin’ you want to, frankly.” Naive and unworldly, his eyes were wide with fascination. The mystery guest would shuffle off later, before pointing an arrowed middle finger at us with a wink and defiant nod: “Now remember–don’t be corrupt!”

Alastair Morgan and I met in early 2018, as his best friend from university doubled as my law and ethics lecturer. The lecturer had a particular teaching style, painting his own stories in the air to engage students. “Have any of you ever heard of Daniel Morgan?” Collective head shaking led to most lessons having at least one pupil pestering for a ‘talk’ which happened in February that year. Later lost in a complicated story centered in Germany, Alastair doubled sometimes as a (begrudging) translator.

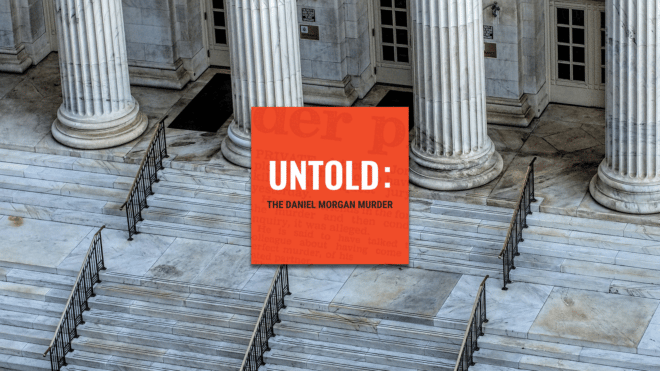

“If you haven’t this story, ask yourself why.” The tag line for the Untold: The Daniel Morgan Murder podcast perhaps succeeded in doing what everyone had failed to do. A viral hit almost overnight, it pulled the case of a notorious murder into the spotlight, while raising uncomfortable questions of the state failure to apprehend those responsible along the way. A private investigator by trade and a father of two, Daniel Morgan was murdered in a London pub’s car park in 1987. Theories surrounding motives include exposure of hornet’s nest of police corruption, potentially via a newspaper article. The remaining family members, including his older brother Alastair, have spent over three decades demanding justice and accountability. Tangled together with the hubris of police corruption and journalistic collusion, there have been five failed murder investigations, one collapsed criminal trial in 2011, and zero criminal convictions since.

Read more: The True Impact of True Crime: a West Cork Case Study

In 2016, journalist Peter Jukes and actor Deeviya Meir began co-producing Untold: The Daniel Morgan Murder with Daniel Morgan’s brother, Alistair Morgan, serving as an additional co-host. The podcast quickly reignited interest in the case. In Untold, a timeline was reconstructed of the tangled twists and turns in the three decades since, including the beginnings of The Daniel Morgan Independent Panel. The Independent panel was ordered just under a decade ago by Theresa May prior to becoming prime minister, to compile a facsimile of documents and interviews, to analyse the role of police corruption and journalistic collusion down the years. Controversy surrounded the panel release in the UK recently, due to the actions by Home Secretary Priti Patel, with fears citing potential for political interference.

The Daniel Morgan Independent Panel reported today, June 16th, 2021. In 1200 pages, a damning indictment was revealed in criticism of the Metropolitan Police. The use of the one ‘rotten apple’ theory was particularly criticised, when it comes to the subject corruption, with phrases like “institutionalised corruption” littering the events of the report being presented.

In a statement, the family welcomed the report, noting the report had “named the sickness that that needs to be addressed.”

A unique partnership gave way to the idea for the podcast. Peter Jukes had originally been a dramatist who wrote scripts at times for the BBC; Meir’s first job had been with Jukes for one of his scripts. “And he said one day at the beginning of the podcast, ‘Why don’t we do just a little podcast about Alastair?’ I met Alastair via Peter, and Alastair told me about his brother then–but I hadn’t heard the story,” said Meir, recounting that mere circumstance had thrown them all together, a coincidence she refers to as one of those “luck syncro-destiny moments that had to happen [. . .] Pieces of a jigsaw puzzle almost came together for us to connect, meet.”

An age of information can be unforgiving for a story belonging traditionally in books, in print. A 24-hour news cycle will fail to explain why this matters to the average reader, the epitome of truth being stranger than fiction.

In a world reliant on the metric of numbers to gauge impact, human costs are so rarely measured. Meir remarked that this story is about the cast of characters, the type of people involved, while mentioning Alastair himself had been going to potentially be an actor, mentioning he had won a place at a prestigious acting school in the UK. He may have been an actor; we will never know, as that ambition was taken away by having to deal with the police over three decades.

The voices of an actor who was never allowed to shine emerge in the silences of conversational lulls in Untold: Leslie, a bitterly sarcastic stereotype of a xenophobic, Brexit supporting 50s housewife; Boris the foul-mouthed Russian former hit man who loves to give political policy critiques; a cockney grandfather disapproving of the youth of today; a young barber flexing his muscles of masculinity to prove he is worthy of a female companion; the European cannibal with a specific love of German beer. (The latter was a joke between friends about a reporter who covered so called cult activity within the area.) A sense of the ridiculous, the whimsical, is perhaps needed at times–a juxtaposition of sorts.

Read more: Ripped from the Headlines: A Review

The Met police have a reputation as “bobbies on the beat”–but this story shatters all of them, and there is a naivety to thinking the police are not imperfect. “Raju [the lawyer for the Morgan family] explained this to me years ago,” says Alastair, unsurprised with a shrug. An age of information can be unforgiving for a story belonging traditionally in books, in print. A 24-hour news cycle will fail to explain why this matters to the average reader, the epitome of truth being stranger than fiction.

As a journalist, I was called a “liar” for recounting the very basics of this story, insulted for daring to use words like “police corruption,” derided for creating a “conspiracy theory” in a post-truth age. Another was so shocked it rendered her usual talkative self speechless.

Twiddling his lockdown-grown beard, his eyes denote a mind in a place far away from this present time. A film has been rewound, back to the vulnerable, isolated days succeeding the murder. Wind back further, a nostalgic smile appears, ghost-like, playing across his face. He scratches his jawline, lost in thought: “I remember travelling across country on my train with my brother, y’know. We were only young, maybe ten, and could get away with running away from the ticket conductor.”

The humour snaps back in mere moments, tangled together with the sentimental at times. The voice quivered by the events of that day: “Lyd . . . can I adopt you?” He points at his partner, Kirsteen, complete with mischievous glint. “If I’m your adopted dad, she can be your adopted mother!”

“Alastair, I am no one’s mother!” is the weary retort, smiling. Having grown up with a complex relationship with a biological father rarely ever there, I cannot put to words how much this meant to me. Topics change between politics and the ridiculous of family life, story swaps spent trying to out do each other, alcohol and time spent travelling. The serious is interspersed and bifurcated from the funny, rendered separate by the low chuckle of a schoolboy caught out.

An age of information can be unforgiving for a story belonging traditionally in books, in print. A 24-hour news cycle will fail to explain why this matters to the average reader, the epitome of truth being stranger than fiction.

Today, the podcast stands as a living archive of an untold story–one with a legacy of its own outside of its niche listener base. The beginning pages of Who Killed Daniel Morgan?, the accompanying book to the podcast authored also by Peter Jukes and Alistair Morgan, points to the need to be a brother’s keeper, a story carried and bottled away within a family unit. But to give away a story could be a release from what Alastair has often referred to as a kind of torture. Meir reflected on this herself: “The podcast was always to give Alastair and the family some way to process all the stuff that has happened to them,” she said, noting her wish that this may give the family a sense of peace. She added that, if he was able, “The story has a life now that Alastair doesn’t need to keep holding on to; he can let it go, almost.”

Speaking ahead of the panel’s release, in expectation of potential revelations, Meir said: “If the call to justice is there, I’m sure we would all take it up.”

“We always said we would do a tie up when the panel reported–we just didn’t imagine it would be this long!” laughed Meir, noting that plans are underway for one last episode. Once the report has been processed publicly and socially, the final episode will then be released as a last special episode. Towards the end of the summer will potentially see the release.

“It’s times like this I miss my mother.” The statement from Alastair comes as a surprise in the smoky haze of outside catering, only just resuming as the UK begins the process of unlocking from COVID-19 restrictions. “To think–I had my mother for sixty-eight years . . .” Mused Alastair, sadly. Isobel Hulsman died just over three years ago, having never seen the panel report about her son published.

Comments

Comments are closed.