PRIDE: Finding Asexual Representation in Indie Audio Drama

In the fall of 2016, I listened to episode 28 of The Bright Sessions.

The next year, I came out to all my friends as asexual (often shortened to “ace”).

This is probably not a coincidence.

In the same way it hides in the back of the LGTBTQIA+ acronym, asexuality is not an obvious orientation. It’s frequently disregarded by those who aren’t queer, often overlooked by the community it’s a part of, and even purposefully excluded on occasion. Aces joke about needing a PowerPoint to come out because so many people don’t know about Asexuality, even the well meaning.

Mainstream media is not well known for its queer representation in general, but the count of canonically ace characters across TV shows is low. Across movies it is, as far as I can tell, zero. Even when the source material has an asexual-identifying character, the adaptation is likely to ignore that (I’m looking at you, Riverdale). While novels are almost certainly the best form of mainstream media if you’re looking for ace rep, the count is also not high. In 2016, it was small enough that despite being an avid reader, I had yet to come across asexuality in fiction.

In fact, I was 21 when I first came across a canonically ace character. Not in a book, movie, or tv show, though. In a podcast.

I nearly dropped my phone listening to “Patient #13 (Chloe) + Friend” when Dr. Bright said, “Some people find asexuality a difficult concept to grasp.” It was the first time I’d heard the term said outside of certain corners of the internet or my school’s Safe Space training, and it meant so much to me.

This was the first time I considered that possibly, my ace-ness was a part of me I wouldn’t have to hide. I’m not exaggerating when I say I was prepared to have everyone except my closest friends assume I was straight until the end of time. But it was at this moment – sitting at my desk, listening to an audio drama – where I started to see that maybe, just maybe, I could be proud of who I was.

Read more: The Bright Sessions Wraps Up While Birthing New Projects

This is what representation does for us. It reminds us that we’re not alone in the world. It reassures us that we’re allowed to exist. Out of a whole world of media, it was this tiny corner of indie audio drama that looked me in the eyes and told me I was allowed to exist. Because while I found representation in The Bright Sessions first, I’ve been finding it again and again across independent audio drama.

I maintain a list of audio fiction shows with ace characters, and at the time of writing, it’s at 43 different shows, 25 of which have in-episode confirmation by characters in the show. There is quite possibly more ace representation in indie audio drama than every other form of media combined.

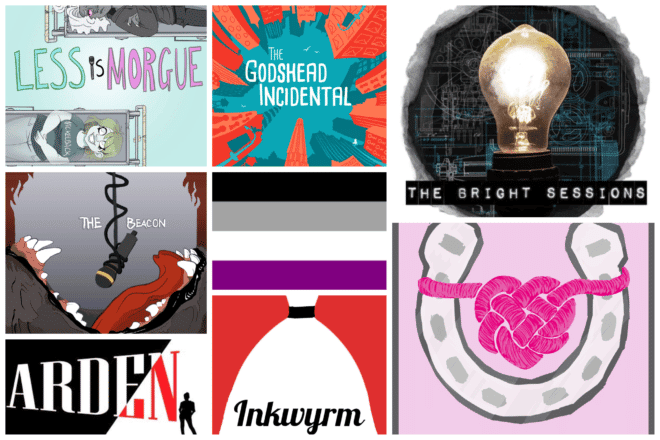

There is The Beacon, a fantasy audio drama about magic powers, giant monsters, and the importance of making friends. In the first episode of season two, main character Bee mentions not understanding why her friend is interested in someone, attributing it by saying, “Maybe it’s just me being asexual.” As someone who’s been in that exact situation, I found the scene incredibly relatable.

There is Love & Luck, a slice of life queer romance story with a touch of magic, told via voicemails. In episode 55, CJ mentions “bonding over asexuality stuff” with Ricardo. I love that their ace identity is not a disruption to possible romance, but actually helps it form. This episode was really inspirational for me, and in a way that is entirely too difficult to explain, it also gave me hope.

There is Inkwyrm, a sci-fi podcast about fashion, aliens, and the indeterminately fabulous future. Robert so boldly states in episode 7, “I’m aromantic asexual. You know that.” He says this like it’s no big deal, channeling the precise confidence I wanted to have myself some day.

Read more: Reimagining 5 podcasts on old audio formats

And more recently:

There’s season 2, episode 7 of Arden, “Rosalind and Pamela are Dead,” where Rosalind gives an extraordinarily relatable rant about her friendship being viewed as a compromise. This is something I’ve personally encountered, and her monologue about the situation hit close to home. Never has this particular sensation been so thoroughly captured in a piece of media for me.

There is Less is Morgue, where Riley brings up being Asexual a number of times, often to fairly unpleasant guests on the show. I love that even the most evil of guests don’t give them a hard time about it, and if any of them come close, Riley shuts them down swiftly. I need to start taking notes.

There is episode 5 of The Godshed Incidental, “In the Dark,” in which protagonist Em questions, “You know I’m ace, right? Ace and aro and undateable?” and is met with a simple “Yes, it’s in your file.” This right here is the ideal response I want to receive when coming out to someone. It’s the dream, and it was so refreshing to hear.

Again and again and again, these shows tell me that it’s okay to be me. They tell others that it’s okay for me to be me. Bee can be at college and trying to fight a monster and also be asexual. CJ and Ricardo can be falling in love and be Asexual. Robert can have an adorable kid and be a doctor and also be asexual.

Maybe I can be a podcaster and engineer and whatever else it is that I am – and also be asexual? Maybe that’s okay?

When society as a whole says the opposite, the message these shows give is incredibly meaningful. Through the simple inclusion of asexual characters, they make me feel that I don’t need to prove I have a right to exist as ace.

Here in 2021, I’m both confident in and proud of my identity. I don’t need this message – but, that wasn’t the case in 2016. Would I have gotten here without these shows? Yes. Am I extremely grateful for the push they gave me to accept who I am? Also yes.

Perhaps it would be slightly more accurate to say this in broader terms:

In 2016, I started listening to indie audio dramas.

The next year, I came out to the world as asexual.

This is, definitely, not a coincidence.

Comments

Comments are closed.